Think with FT

Think with FT

Think with FT helps you quickly and easily understand who and what FT articles are talking about. Uncover the information you didn’t realise you needed to know in order to get the most from the Financial Times.

Think with FT helps you quickly and easily understand who and what FT articles are talking about. Uncover the information you didn’t realise you needed to know in order to get the most from the Financial Times.

The marketing of “Theland” milk powder says it all — cows graze on emerald grass below white clouds shaped like New Zealand. “A Cow per Acre” reads the slogan on the package.

For anxious mothers in China’s crowded cities, Theland’s promise of space and quality in faraway places comes through loud and clear. They are not the only ones beguiled. Chinese businessmen, tired of thin margins at home, are lured by the promise of big tracts of land overseas.

Pengxin, a little-known Shanghai real estate developer that owns Theland, will become the world’s largest private landowner if Australia’s authorities clear its most ambitious bid yet: to gain control of the grazing lands of the S Kidman & Co cattle empire. That, plus holdings in New Zealand, make Pengxin the boldest of Chinese corporations investing in land, and has helped trigger a backlash.

“China has seen fast development; lots of people have made money and now they don’t know where to put it,” says agriculture expert Li Guoxiang of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, explaining why Chinese invest in land overseas. “It’s part of the desire to move capital overseas and diversify choices … But we worry about tensions.”

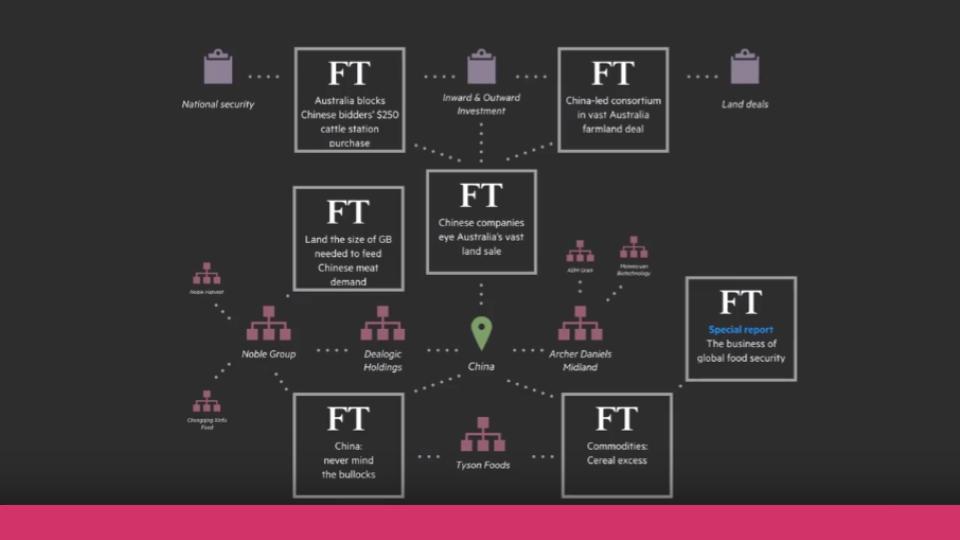

The Financial Times, in a series of reports, is examining governments and private investors’ increasing interest in grand-scale land deals. With the commodity supercycle ending, land — the ultimate resource — could either become the next big thing or the source of cross-border disputes.

Pengxin stands out among Chinese companies investing in land overseas because of the size of its purchases and the scrutiny it has encountered. It is a midsized real estate and chemicals company based in Shanghai. In addition to its agricultural investments, it also owns mines overseas.

The group is the lead bidder for 77,000 sq km of Kidman grazing lands that make up the largest private property on earth. In November, Australia blocked the A$350m ($257m) sale on security grounds. Pengxin rebid after excluding lands near an international weapons testing ground; but last month the sellers reopened bidding to add a domestic competitor.

Pengxin’s bid for Kidman draws on its experience as China’s largest land investor in New Zealand. But its expansion there has reached a limit only months after it announced plans to double its Kiwi assets to NZ$1bn ($670m) or 50 farms.

“We anticipated that investing in New Zealand farmland would not be easy but, in reality, it has been more challenging than we thought,” Terry Lee, president of overseas investment for Pengxin, wrote in response to written questions from the FT.

In September, New Zealand vetoed Pengxin’s purchase of a 138 sq km sheep farm, Lochinver Station. A Pengxin subsidiary promptly pulled out of a NZ$43m deal to buy 10 other farms.

The veto came as New Zealand imposed taxes on investment properties and stiffer requirements on foreign buyers. Popular resentment had risen after property documents, leaked to New Zealand media, showed buyers with Chinese surnames accounted for half the purchases of Auckland homes worth more than NZ$1m.

Similarly in Australia, Canberra is reviewing foreign investment rules and has cut the threshold for approval of foreign acquisitions of rural land from A$252m to A$15m. A new registry of foreign-owned agricultural land goes public this year.

As China’s urban sprawl consumes and pollutes its farmland, Beijing has given tacit blessing to agricultural investment overseas. Still, actual deals are few and far between.

They range from vineyards in France, Chile or Argentina to state farm investments in large Ukrainian tracts and agricultural pilot projects in Africa. Private Chinese entrepreneurs approach overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia to invest in oil palm plantations and vegetable farms.

Australia and New Zealand are top destinations because foreigners can own land outright, but resentment over Chinese investors buying residential property has curdled the political environment.

Buying farmland “down under” makes sense for Chinese investors as slowing growth eliminates business returns at home. Tracts are large, costs are low and title is relatively uncomplicated. Chinese consumers pay a premium for imported food, especially infant formula.

Pengxin’s purchase of New Zealand’s struggling Crafar Farms in 2012 at first raised hackles. But the company engaged with native Maori groups and hired veteran dairymen from both countries. Founder Jiang Zhaobai, an architectural engineer turned entrepreneur, energetically flew well-heeled Chinese tourists around New Zealand. “They’ve earned their spurs. They’ve been dragged through the mud and come out again,” says one observer who closely tracks foreign investment in New Zealand.

--- title: 'The Great Land Rush: China’s Pengxin hits overseas hurdles' primaryTheme: Land Deals terms: - Pengxin - S Kidman & Co - Chinese Academy of Social Sciences - Jiang Zhaobai layout: article permalink: /article-2 ---

The marketing of “Theland” milk powder says it all — cows graze on emerald grass below white clouds shaped like New Zealand. “A Cow per Acre” reads the slogan on the package.

For anxious mothers in China’s crowded cities, Theland’s promise of space and quality in faraway places comes through loud and clear. They are not the only ones beguiled. Chinese businessmen, tired of thin margins at home, are lured by the promise of big tracts of land overseas.

Pengxin, a little-known Shanghai real estate developer that owns Theland, will become the world’s largest private landowner if Australia’s authorities clear its most ambitious bid yet: to gain control of the grazing lands of the S Kidman & Co cattle empire. That, plus holdings in New Zealand, make Pengxin the boldest of Chinese corporations investing in land, and has helped trigger a backlash.

“China has seen fast development; lots of people have made money and now they don’t know where to put it,” says agriculture expert Li Guoxiang of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, explaining why Chinese invest in land overseas. “It’s part of the desire to move capital overseas and diversify choices … But we worry about tensions.”

The Financial Times, in a series of reports, is examining governments and private investors’ increasing interest in grand-scale land deals. With the commodity supercycle ending, land — the ultimate resource — could either become the next big thing or the source of cross-border disputes.

Pengxin stands out among Chinese companies investing in land overseas because of the size of its purchases and the scrutiny it has encountered. It is a midsized real estate and chemicals company based in Shanghai. In addition to its agricultural investments, it also owns mines overseas.

The group is the lead bidder for 77,000 sq km of Kidman grazing lands that make up the largest private property on earth. In November, Australia blocked the A$350m ($257m) sale on security grounds. Pengxin rebid after excluding lands near an international weapons testing ground; but last month the sellers reopened bidding to add a domestic competitor.

Pengxin’s bid for Kidman draws on its experience as China’s largest land investor in New Zealand. But its expansion there has reached a limit only months after it announced plans to double its Kiwi assets to NZ$1bn ($670m) or 50 farms.

“We anticipated that investing in New Zealand farmland would not be easy but, in reality, it has been more challenging than we thought,” Terry Lee, president of overseas investment for Pengxin, wrote in response to written questions from the FT.

In September, New Zealand vetoed Pengxin’s purchase of a 138 sq km sheep farm, Lochinver Station. A Pengxin subsidiary promptly pulled out of a NZ$43m deal to buy 10 other farms.

The veto came as New Zealand imposed taxes on investment properties and stiffer requirements on foreign buyers. Popular resentment had risen after property documents, leaked to New Zealand media, showed buyers with Chinese surnames accounted for half the purchases of Auckland homes worth more than NZ$1m.

Similarly in Australia, Canberra is reviewing foreign investment rules and has cut the threshold for approval of foreign acquisitions of rural land from A$252m to A$15m. A new registry of foreign-owned agricultural land goes public this year.

As China’s urban sprawl consumes and pollutes its farmland, Beijing has given tacit blessing to agricultural investment overseas. Still, actual deals are few and far between.

They range from vineyards in France, Chile or Argentina to state farm investments in large Ukrainian tracts and agricultural pilot projects in Africa. Private Chinese entrepreneurs approach overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asia to invest in oil palm plantations and vegetable farms.

Australia and New Zealand are top destinations because foreigners can own land outright, but resentment over Chinese investors buying residential property has curdled the political environment.

Buying farmland “down under” makes sense for Chinese investors as slowing growth eliminates business returns at home. Tracts are large, costs are low and title is relatively uncomplicated. Chinese consumers pay a premium for imported food, especially infant formula.

Pengxin’s purchase of New Zealand’s struggling Crafar Farms in 2012 at first raised hackles. But the company engaged with native Maori groups and hired veteran dairymen from both countries. Founder Jiang Zhaobai, an architectural engineer turned entrepreneur, energetically flew well-heeled Chinese tourists around New Zealand. “They’ve earned their spurs. They’ve been dragged through the mud and come out again,” says one observer who closely tracks foreign investment in New Zealand.

Guided by Mr Lee, a private equity investor who moved to New Zealand in 2003, Pengxin is building its own integrated dairy business. That is a direct challenge to Fonterra, the world’s largest dairy exporter which processes and markets milk on behalf of thousands of Kiwi farmers.

“Our aim is to satisfy demand from the Chinese middle class for high quality dairy products while exploring a complete supply chain model for New Zealand dairy products,” Mr Lee wrote.

Pengxin had no background in agriculture in China before 2013 when it took over Dakang, a struggling pig breeder listed on the Shenzhen exchange, and began expanding its livestock business. It purchased a soya bean property in Bolivia in 2005 at the height of Chinese soya bean speculation.

“The property sector is not performing well and many companies want to change their focus,” said private equity analyst Ruan Yifei. “Farming and animal husbandry is blooming and very promising in China. Their reasons for investing are right.”

Pengxin’s blueprint for integrated dairy and mining businesses makes sense. But its internal structure is difficult to grasp and has contributed to distrust in its target markets.

Like many Chinese property entrepreneurs, Mr Jiang’s businesses span a range of sectors. He started out by building factories around Shanghai, then branched into chemicals, real estate and mining before moving into agriculture and overseas land. His listed companies include Hong Kong-listed EverChina. Before Mr Jiang’s investment, that stock was flagged by regulators because its share ownership was concentrated in too-few hands, and for other problems.

Pengxin has raised funds through the high-interest shadow banking market by issuing trust products, a common strategy when housing prices were soaring. As markets slumped, it reshuffled overseas mining and land assets into its listed units. An article in China’s Securities Times newspaper in 2014 described the company as a “hurtling capital train” that must continue growing to move forward.

Pengxin bought 55 per cent of Shenzhen-listed Dakang in 2013 via several wholly-owned subsidiaries registered in a Tibetan town bordering Mount Everest. Other shareholders are indirectly related, according to public records, in effect giving Pengxin greater control over Dakang.

It is now trying to transfer its New Zealand assets into Dakang. That decision cost the company some of its carefully cultivated good will in New Zealand, because it began the transfer while the government was still reviewing the Lochinver Station purchase.

The company posted the properties on the internet auction site Trade Me to comply with a legal requirement to offer them to New Zealand citizens, raising some concerns that it had tried to shortcut the process.

The reshuffle was driven by internal dynamics but it hurt the company in New Zealand, and led directly to the veto of the Lochinver Station purchase. Similar mismatches between its internal needs and international perception could hamper Pengxin in its mammoth bid for Australian land.

“China is a real problem for Australia and New Zealand — the perfect partner on the surface with huge markets, huge growth potential and very clear needs from these countries,” says Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese studies at King’s College, London.

"But underneath, China remains alien in terms of fundamental values and political beliefs. Unless that changes in China, it will never be an easy relationship and public ambiguity will continue."